There have been frequent media reports on possible famine and starvation in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) in 2021. [1] This paper assesses these accounts using available open-source information and provides an overview of the food security situation in the DPRK.

Key Takeaways

-

As of mid-2021, while the DPRK's food distribution system appears to have been significantly constrained, reliable open-source information could not be found to confirm nationwide food insecurity. Available information suggests that, rather than a nationwide lack of food, food insecurity exists in certain regions and among certain populations.

-

The impacts of food insecurity appear to differ from region to region in the DPRK. The inner northeastern regions whose economies rely on land-based trading with the People's Republic of China (China) appear to have been hit harder than the northwestern regions where seabased trading with China has expanded since May 2021. This may be attributable to landbased border closures and the lockdown of cities.

-

As for the domestic food supply system, fishery operations have faced significant problems since 2020. Most fishing vessels appear to have suspended operation at least during the period between late November 2020 and June 2021. While fishery operations reportedly resumed in June or July 2021, the DPRK might need more time until fishing vessels return to full operation.

-

As for crop harvesting, the DPRK experienced difficulties in acquiring necessary foreignsourced items, such as improved seeds, fertilizers, herbicides, pest control chemicals, farm machinery and spare parts. As a result, the yield forecast for some crops in 2021, especially rice, is below the 5-year average expectation. [2] On the other hand, the DPRK enjoyed generally favorable weather conditions for growing crops in June and early July 2021. However, harvesting could be negatively affected by the prolonged drought that has prevailed in most of the country since mid-July and the heavy rainfall and flooding in South Hamgyong Province in early August, more of which is expected in the coming months. Unless the DPRK imports more food or receives external food aid, the country's food supply system could be strained further.

-

Food security in the DPRPK is deeply connected to the implementation of counter-pandemic measures. For the DPRK to import food or receive food aid from the other countries in earnest, counter-pandemic measures, including vaccination of the population (which of necessity would require some opening of borders) will be essential. The speed with which counter-pandemic measures are implemented will likely continue to affect the DPRK's efforts to secure a stable supply of food.

-

The DPRK's food security has also been constrained by international sanctions which have been increasingly strengthened. Since 2017, it has become especially challenging for the country to import foreign-sourced items for agricultural use, including machinery and spare parts as well as certain chemical products for producing fertilizers. [3] In order for the DPRK to resume foreign trading, the country will need to prioritize strengthening diplomatic relationships with trading partners interested in expanding legitimate trade, especially China.

-

Under the "people first principle", food security is defined by the government of the DPRK and by the Workers' Party of Korea as a top priority. Since June 2021, Kim Jong Un and the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK) emphasized the necessity of securing sufficient food supply (see Section I). This likely reflects the view that food security is indispensable to solidifying political and social stability. As such, food security will continue to be a dominant issue for the DPRK.

Introduction

On 15 June 2021, during the 3rd Plenary Meeting of the 8th Central Committee of the WPK, Kim Jong Un acknowledged serious problems in the national food supply, stating that "the people's food situation is now getting tense as the agricultural sector failed to fulfill its grain production plan due to the damage by typhoon last year". [4] According to Korean Central Television (KCTV), one of the items on the agenda during this meeting was "establishing an emergency policy on overcoming the current food crisis" (당면한 식량위기를 극복하기 위한 긴급 대책을 세울데 대하여). [5] Kim's statement and the report from KCTV deepened widespread speculation among external observers and international media about a possible famine in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK).

In a report dated 1 March 2021, U.N. Special Rapporteur on North Korean Human Rights Tomás Ojea Quintana warned of a coming "serious food crisis", citing concerns about restrictions on trade with China, limited market activities, lack of humanitarian support, ongoing implementation of sanctions and damage to agriculture caused by typhoons and floods. He also referred to reports of deaths by starvation in the DPRK. He reported that the increased food insecurity was caused by the prolonged COVID-19 prevention measures which had resulted in a drastic decline in trade and commercial activities and severe economic hardship among the general population. [6]

This was followed by the 2021 Global Report on Food Crises dated 5 May 2021 published by the Global Network against Food Crises (GNFC), which identifies five phases of acute food insecurity as: (1) none/minimal; (2) stressed; (3) crisis; (4) emergency; and (5) catastrophe/famine. In that report, the DPRK is characterized as being in a "food crisis" phase, which is defined as households having food consumption gaps that are reflected by high or above-usual acute malnutrition or which are marginally able to meet minimum food needs but only by depleting essential livelihood assets or through crisis-coping strategies. [7] While the DPRK was not categorized as being in the most serious phase of facing famine, the reports notes data gaps and insufficient evidence in making its assessment.

Several knowledgeable experts with contacts within the DPRK have argued that, in assessing the DPRK's severe food situation, one should differentiate between national famine and food shortage among the poor due to income gaps between the rich and the poor (see Section VIII).

Regional Differences in Food Supply

Food Prices

In April 2021, two months before the statement by Kim Jong Un regarding the DPRK's "tense" food situation, the Russian Ambassador to the DPRK Alexander Matsegora offered a similar observation in an interview with the press. However, in a slightly softened tone, he referred to the general availability of basic foodstuffs:

We see with our own eyes how the prices for many industrial and food products have grown noticeably, and the imported assortment has practically disappeared from the shelves. But at the same time, there is no shortage in the category of basic foodstuffs, prices, if they have grown, then moderately and not for all items. So, for example, rice still costs 4,500 won per kilogram, for a dollar now they give 7,000 won against 8,300 before the pandemic. [8]

Ambassador Matsegora's observation is consistent with information provided by two non-profit organizations with contacts in the DPRK: Asia Press (also known as "Asia Press Network") and Daily NK.

The Japan-based Asia Press [9] has been reporting at least since 2017 on the prices of key commodities in the DPRK markets (e.g. diesel oil, gasoline oil, rice and corn) and on currency exchange rates between the DPRK won and the Chinese yuan and US dollar. [10]

While acknowledging the increasing difficulty of obtaining real time information from inside the DPRK, [11] Asia Press has reported that the market price of domestically produced rice in North Hamkyung Province and Ryanggang Province, the two provinces along the northeastern border with China, remained relatively expensive but stable during April 2021, ranging from 4,000 to 4,300 won per kilogram.

Daily NK, a non-profit organization based in the Republic of Korea, also reported 4050- 4300 won per kilogram for rice available in the city of Hyesan, which is located in Ryanggang Province. In April 2021, Daily NK reported slightly lower prices of rice ranging from 3,600 to 3,950 won per kilogram in Pyongyang and Sinuiju, which are located relatively close to the Western coast of the DPRK.

Figure 1: Map of the DPRK. Source: World Atlas

Since the DPRK closed its borders and suspended trading with China in January 2020, price levels in the inland border regions of Ryangang Province and North Hamkyung Province have been generally higher than those in Pyongyang and Sinuiju in the northwestern region which are close to the Nampo Port, the main gateway for maritime trade with China. The Nampo Port was intermittently closed between January 2020 and early 2021 but appears to have resumed operation in April 2021. The price difference may reflect the relative difficulty in obtaining China-sourced commercial commodities and foodstuff in the northeastern inland border region as compared to the northwestern region during the pandemic.

Both Asia Press and Daily NK reported relatively stable prices of rice and corn up until May 2021.

Signs of Food Insecurity

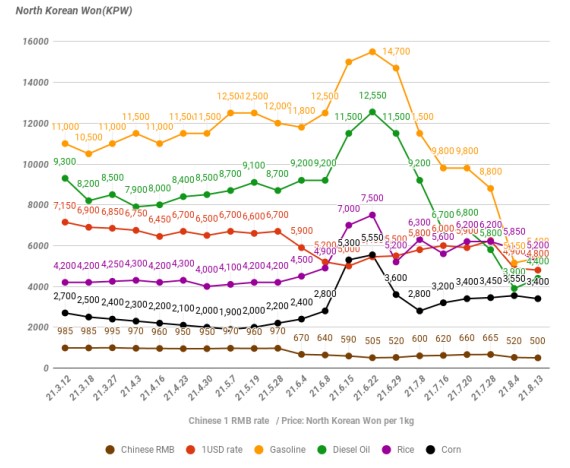

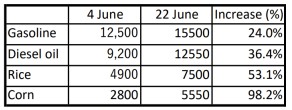

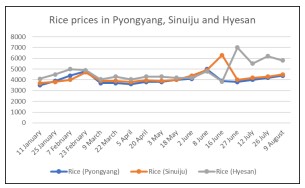

In June 2021, the market prices of key commodities suddenly fluctuated sharply (Figure 2). Based on information from three DPRK provinces bordering with China (North Hamkyung Province, Ryanggang Province and North Pyongang Province), [12] Asia Press reported hikes in the price of corn by 98%, the price of rice by 53%, the price of diesel oil by 36% and the price of gasoline by 24% in the first two weeks of June (Figure 3). According to Daily NK, commodities prices also surged in Pyongyang and Sinuiju (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Fluctuation of prices of key commodities and of currency exchange rates in the DPRK between 12 March and 13 August 2021. Source: Asia Press [13] (chart cited with permission of Jiro Ishimaru, Asia Press)

Figure 3: Price hikes of key commodities in the DPRK, June 2021. Source: Asia Press (chart compiled by author) [14]

Figure 4: Rice prices in Pyongyang, Sinuiju and Hyesan, 11 January to 9 August 2021. Source: Daily NK (the chart was compiled by the author) [15]

The exact causes of the June price hikes are unclear. Experts from the Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU), a think tank of the Ministry of Unification of the Republic of Korea (ROK), speculated that the rapid increase in the market price of rice appeared to have been "the result of a lack of supply", while referring to other possible causes, such as the DPRK's intervention to restrict market prices and the limited capacity of the public distribution systems. [16]

It bears noting that on 15 June, in the middle of the price hikes, Kim Jong Un acknowledged the country's food problem and decided on "an emergency policy on overcoming the current food crisis", which suggested an emergency delivery of food to the people. [17]

After hitting a peak around 22 June, prices began to decline sharply. By early July, most of the key commodity prices had dropped close to the levels of 28 May, or even below, according to reports by Asia Press and Daily NK (Figures 2 and 4). On 8 July, Asia Press reported information from DPRK authorities that corn prices had fallen in the cities of Chongjin and Hoeryong in North Hamkyung Province after emergency food was supplied. Although other grain products remained mostly unavailable in these cities, stress on the food supply system was relieved at least to some extent. [18]

Simultaneously, Asia Press reported an unusual appreciation of the DPRK won against the Chinese yuan and the US dollar in June (Figure 2). While the exact causes of this phenomenon are also unknown, there was speculation that the DPRK government might have prohibited the use of foreign currencies in domestic markets [19] and that trade-related institutions and individuals in the DPRK may have rushed to sell their foreign currency when the government unveiled new measures to restrict foreign trade. [20] These speculations could not be corroborated.

Foreign Trade and Food Supply

Impact of Trade on Food Supply

Since 2020, the volume of DPRK-China trade has fluctuated. In most North Korean cities, the changes in price levels correlated with these changes.

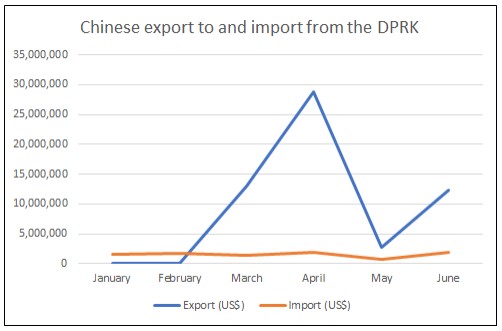

The price fluctuations in June 2021 were preceded by fluctuations in the volume of Chinese exports to the DPRK between May and June. In June, food and commodity prices dropped sharply after a gradual resumption of maritime transportation between the DPRK and China. This confirms the suggestion by U.N Special Rapporteur on North Korean Human Rights Ojea Quintana that the closure of the China-DPRK border had contributed to food supply problems. [21]

According to official data from Chinese customs statistics, Chinese exports to the DPRK recorded close to zero in January and February 2021, but began to increase in March. [22] On 4 March 2021, during the 13th Plenary Meeting of the Standing Committee of the 14th Supreme People's Assembly, the DPRK adopted a "Law on Disinfection of Imports" to demonstrate the country's intention to prepare for importing foreign products by disinfecting foreign-sourced items without having to wait for an end to the pandemic. [23] Chinese business people in the city of Dandong reportedly expressed optimism that China-DPRK trade might resume soon. [24]

In April 2021, Chinese exports to the DPRK picked up pace and the monthly export value reached US$ 28,751,321. However, exports dropped suddenly and sharply in May to US$ 2,713,827, an almost 91% decrease in one month. Reportedly, sometime in late April or in May, the DPRK authorities tightened border control again and suspended crossborder trading in response to the global rise in COVID-19 infections, which may account for the sudden and sharp decline in trade volume in May.

In June, however, the DPRK again loosened its restrictions on trading with China. Chinese exports to the DPRK began to pick up pace again and increased up to US$ 12,318,424 in June, close to the March export value of US$12,977,822. According to those involved in China-DPRK trade, this may have been attributable to the fact that the DPRK carefully resumed trading in small volumes through Nampo Port in June. [25]

Figure 5. Chinese exports to and imports from the DPRK, January-June 2021 (unit: US$). Source: Chinese customs statistics [26]

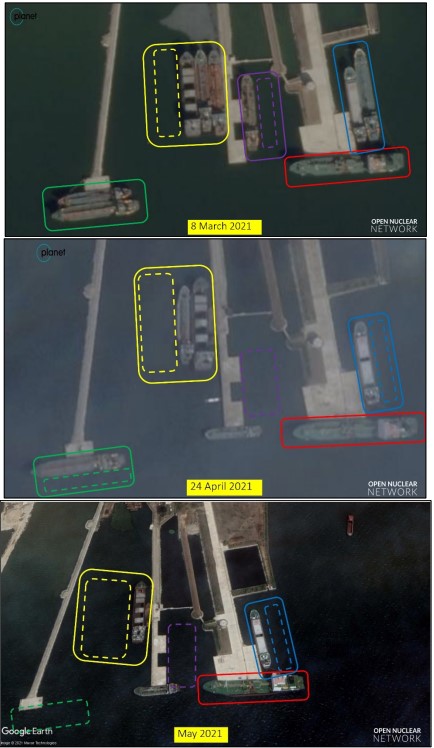

Satellite imagery confirms that the levels of maritime transportation of vessels at Nampo Port remained at a low level and many vessels remained docked at least from December 2020 through March 2021. However, activity gradually resumed in April, slowed down in May and slowly picked up again in June (Figures 6 and 7).

Figure 6. Overview of the Nampo Port, December 2020. Image: Google Earth

Figure 7. Fixed-point monitoring of piers near the oil and lubricant storage area of the Nampo Port, December 2020-May 2021. Images © 2021 Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved; Google Earth (December 2020 and May 2021). At the three piers near the oil and lubricant storage area of Nampo Port, most vessels remained stationary between December 2020 and early March 2021. Vessels gradually resumed operation thereafter.

According to Eun-Lee Joung, a research fellow at KINU, as of mid-June, twenty-two DPRKChina land customs clearance posts were preparing for a border opening by repairing and expanding their facilities. [27] In the city of Dandong, China, a key gateway for land-based trade with the DPRK, new facilities, emblazoned with the name "Epidemiological Survey Zone (流行病学调查区)" had been established in the Entry-Exit Border Inspection Zone at least since March 2021, according to video footage from NHK [28] and Planet Labs high resolution satellite imagery (Figure 8). The establishment of a new quarantine zone indicate preparations by the two countries to resume land-based transportation.

Figure 8. The newly established Epidemiological Survey Zone in the Entry-Exit Border Inspection Zone, Dandong, China, March 2021. Image: Google Earth

In the satellite imagery, the presence of vehicles could barely be observed in the customs areas in Dandong and Sinuiju as of June 2021, which suggests that the border opening was not imminent (Figure 9). There is no information yet to confirm the resumption of land-based bilateral trade in full swing. According to Mitsuhiro Mimura, Senior Research Fellow of the Japan-based think tank Economic Research Institute for Northeast Asia, as of 14 July, the two countries had yet to reach an agreement about quarantine measures to be applied to the truck drivers. [29]

Figure 9. Comparison of the presence of vehicles in the customs area in Sinuiju between November 2019 and June 2021. Images: © 2021 Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission; Google Earth (November 2019)

There have also been signs of the DPRK’s preparation to resume air transportation near Sinuiju. Colin Zwirko of NK Pro, a Seoul-based DPRK research platform, has found thorough satellite imagery analysis that, since February 2021, the DPRK has been transforming the Uiju military-civilian airport, located about 13 kilometers northeast from Sinuiju, into a center for the disinfection of goods. Zwirko assessed that this was in preparation for resuming large-scale trade with China. [30] However, it is unclear when the altered airfield may be activated (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Alteration of the Uiju airport, as of 13 August 2021. Images: © 2021 Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission

As the DPRK has refrained from receiving foreign-sourced food supply due to the pandemic, food security is dependent on the implementation of counter-pandemic measures in this country. Such measures, including vaccination of the population, might hold the key for the DPRK's resumption of trade in full earnest. The speed of implementation of counter-pandemic measures will likely continue to affect the DPRK's efforts to secure a stable food supply from other countries.

Hyesan: A Case Study on the Impact of Trade on Food Supply

The city of Hyesan in the Ryanggang province has served as a key node in land transportation between the DPRK and China. Since around November 2020, there have been reports on the severe economic conditions and lack of food in Hyesan and starvation and death in the city. Some media have reported the dire circumstances in Hyesan as a possible sign of nationwide starvation or famine.

In contrast to other cities, the commodity prices in Hyesan reportedly remained at a high level until at least early August (Figure 4). On 27 June, Daily NK reported a local rice price of 7,000 won per kilogram in Hyesan, almost twice the price of rice in Pyongyang (3,800 won per kilogram). Asia Press reported that food delivery had been delayed in Hyesan and noted that regional differences became noticeable in the recovery of price levels.

This city’s economy has suffered heavily due to the DPRK’s border closure. Reportedly, Hyesan was locked down for twenty days in November 2020. [31] Satellite imagery confirms the unusual almost complete lack of vehicle presence in front of the train station at that time (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Comparison of the presence of vehiclesin front of the Hyesan train station between March 2019 and November 2020. In March 2019, many vehicles were present in front of the station, while in November 2020, almost no vehicles could be observed at the same location. Images: Google Earth

Reportedly, Hyesan was locked down again in February 2021. Several media reported that the lockdown was likely based on a political decision to crack down on illicit trade with China which violated the DPRK's decision to close its borders in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19 virus into the country from China. [32] Asia Press reported deaths in Hyesan due to the lack of medicine and food at that time. [33] While these accounts could not be corroborated, 3-meter resolution satellite imagery from late July 2021 points to a low level of vehicle activity near the Hyesan train station, which indicates that the city's economic activities likely remained at a low level.

It should be noted, however, that Hyesan appears to have suffered particularly severe economic difficulties compared to other cities. It should also be noted that available information suggests that the shortage of food and other commodities in Hyesan was due to the lockdown of the city and the suspension of cross-border trading, rather than to indications of national starvation. Economic and food insecurity in Hyesan should not be assumed to represent that of other cities.

Domestic Food Supply

Fishery Operations

There are also considerable challenges in the domestic supply of foods, in particular, with respect to fishery operations. In 2020, DPRK authorities reportedly restricted fishery operations on the sea to prevent the spread of COVID-19. In the Chongjin port, one of the major fishing ports on the DPRK's east coast, satellite imagery shows that most of the fishing vessels appear to have remained in the harbours at least between November 2020 and June 2021, indicating that they may not have operated during this period (Figures 12- 14).

Figure 12. Overview of the Chongjin Port showing the eastern and western harbours for fishing vessels, May 2021. Images: Google Earth

Figure 13. Fixed-point observation of the western harbour for fishing vessels in the Chongjin Port, November 2020 - June 2021. Images © 2021 Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved; and Google Earth (November 2020, March and May 2021)

Figure 14. Fixed-point observation of the eastern harbour for fishing vessels in the Chongjin Port, November 2020 to June 2021. Images © 2021 Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved; and Google Earth (November 2020, March and May 2021)

In an article dated 13 July, Eun-Lee Joung noted that fishery operations had resumed and that the price of fish products had declined, but that the price of fish was still almost five times the pre-pandemic price. While this information has yet to be confirmed, the DPRK might need more time until the fishing vessels return to full operation. [34]

Crop Harvesting

As of early August, the prospects for crop harvesting are unclear because of the unpredictable weather conditions, including drought, heavy rainfall and flooding.

In its report to the United Nations dated June 2021, the DPRK government acknowledged that, already in 2018, the national goal to produce 7 million tons of cereal could not be achieved. [35] Reportedly, the crop production in 2018 was about 4.95 million tons, the lowest since 2008. According to the DPRK, the main reasons for the decreased production level were natural disasters, weak resilience, insufficient farming materials and low level of mechanization.

The DPRK noted difficulties in acquiring foreign-sourced items necessary for agriculture and stated that, "The continued sanctions and blockade creates serious obstacles to the DPRK government in achieving the SDGs." [36] The U.S. Department of Agriculture also noted the DPRK's difficulties in acquiring necessary inputs, such as improved seeds, fertilizers, herbicides, pest control chemicals, farm machinery and spare parts, due to the border closure during the pandemic. [37]

In its publication dated July 2021, Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) warned that a large portion of the DPRK's population suffered from low levels of food consumption and very poor dietary diversity. FAO assessed that the total domestic utilization of cereals, soybeans and potatoes would exceed domestic availability of these foods, with an estimated supply gap at about 880,000 tonnes. According to FAO, the DPRK population could experience a harsh lean period, particularly from August to October, if this gap is not adequately covered through commercial imports and/or food aid. [38]

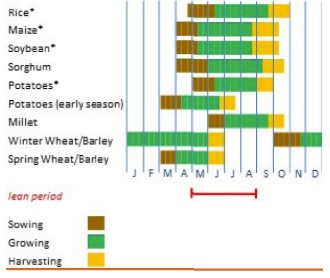

FAO's assessment was based on the assumption that the main seasonal crops would become available for consumption in October (Figure 15). In June and early July, the DPRK enjoyed generally favorable weather conditions for growing crops, which was reportedly sufficient to fully recharge irrigation water reservoirs. [39] Chinese customs statistics show that, in April and May, before the rice and other crop planting began in June, the DPRK extensively imported products related to crop planting and harvesting, including fertilizer and insect killers. [40] The US Department of Agriculture assessed on 27 July 2021 that crop productivity was expected to be near or above historical averages, but also noted that there was a wide range of possible yield outcomes depending on subsequent weather conditions. [41]

Harvesting could be negatively affected by the prolonged drought the DPRK experienced since mid-July. On 26 July, the Korea Central News Agency (KCNA) reported that the continuing drought had damaged rice and corn leaves. According to KCNA, the mean precipitation as of mid-July stood at the second lowest in the records of the national meteorological observation since 1981.

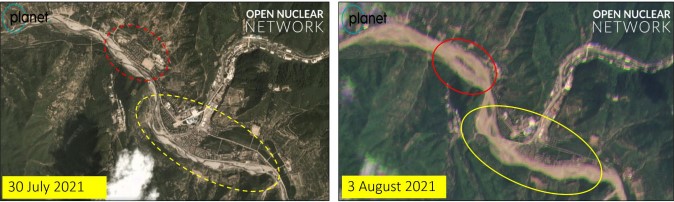

The DPRK is also concerned about floods and heavy rainfall in the coming months which may cause critical damage to the harvest. On 5 August 2021, Korea Central Television (KCTV) reported that Buryong County in North Hamgyong Province and Sinhung County in South Hamgyong Province had experienced heavy rainfall and flooding, which had caused extensive damage to the regions, including anywhere from a few to several millions of square meters of agricultural land having been buried, flooded or washed out. [42] Planet Labs satellite imagery confirms extensive damage to the towns and agricultural fields along the river (Figure 16). [43]

Severe weather conditions could alter the prospect of crop harvesting in the next few months.

Figure 15: The DPRK's crop calendar showing the lean period for each crop. Source: FAO [44]

Figure 16: Example of flood damage to towns and agricultural fields in the South Hamgyong Province (aka. Hamgyong-namdo), August 2021. Images © 2021 Planet Labs Inc. All Rights Reserved

Status of Food Insecurity: Nationwide Starvation or Poverty Among Certain Regions/Populations?

As described above, the country's food supply has been facing serious problems which will likely continue for some time. Nevertheless, thus far, no conclusive evidence is available to confirm that nationwide starvation was taking place as of 14 August 2021. The DPRK's food insecurity concerns not only the supply and production of food but also the distribution of food. Available information points to the most likely contributing factors of food insecurity as the border closure and the lockdown of cities, rather than a nationwide lack of a sufficient amount of food. This observation is based on the following:

-

The economy of the northeastern inland border region appears to have been hit harder than in the western region which currently serves as a gateway for maritime trade with China. Food price instability in June was more or less stabilized by the end of July, which demonstrates that the DPRK still retained some capacity to supply food to the local markets, whether through the release of emergency reserves or the import of food from neighboring countries.

-

The DPRK appears to have retained at least some level of food stocks. For example, when the DPRK increased its trade with China in April 2021, the country imported from China 283.8 tons of butter. [45] Given that butter is not commonly consumed by North Koreans, [46] if the Chinese statistics are correct, the imported butter was likely intended for use in the food processing industry, which indicates the existence of some food stock or the inflow of food supply from other countries. It is possible that the food processing industry could be still operating albeit at a low level.

Several experts and journalists who obtained information from their contacts within the DPRK have argued that the problems in the food supply system have to do more with income gaps within the country. Eun-Lee Joung contends that "a key problem for the North Korean economy lies in the widening economic gaps between rich and poor, cities and rural areas, and successful and failed firms." [47]

Similarly, Mimura contends that, "[e]ven though there are people who cannot buy food due to lack of money, there is never a total lack of food in the city. The problem of the lack of access to food [among people] should be seen as a poverty problem." [48] According to Mimura, who has made multiple visits to the DPRK and has interacted with DPRK economists, North Koreans are able to buy food and other commodities through local markets or transactions between individuals, outside the framework of the socialist planned economy.

Asia Press has also reported that the new wealthy segment of the population, known as "donju," were buying up food, that merchants were not willing to sell food at low prices and that those who did not have enough money could not buy food and were starving. [49]

While conclusive data is not available to corroborate these observations, available information shows that, as of mid-August, the food prices continued to stay at a more or less stabilized level in Pyongyang and in North Hamkyung Province, Ryanggang Province, North and Pyongang Province (figures 2 and 4). This indicates availability of food stock and a functional food supply system still operating in the country. DPRK resident reportedly said that as of early August, "traders are bringing in more food from other areas [into two provinces bordering China, namely North Hamkyung Province and Ryanggang Province]." [50]

Nevertheless, these experts also unanimously agree that, despite these observations, the DPRK has been struggling to maintain its food supply system. [51] According to Asia Press, in North Hamkyung Province and Ryanggang Province, food remained expensive as of early August. [52] Reportedly, most of the white rice being sold in the local market was Chinese rice, and flour from Russia was being sold in the market. [53] If these reports are true, DPRK authorities must have tried to stabilize food prices by receiving food aid and food imports from China and Russia.

In addition, the DPRK likely released military and emergency reserves based on the "emergency policy on overcoming the current food crisis" which was decided during the 3rd Plenary Meeting of the 8th Central Committee of the WPK in mid-June. The DPRK is certainly not free from the risk of significant food shortage in the coming months. In order to secure a stable food supply, the country would need to import food or receive food aid from other countries to make up for the gap between supply and demand in local markets.

Food Security and Its Political and Social Implications

The prospect of severe food insecurity has been a dominant agenda for Kim Jong Il.

On 15 June 2021, during the 3rd Plenary Meeting of 8th Central Committee of the WPK, Kim Jong Un said, "having a good crop is a militant task our Party and [the] state must fulfill as a top priority issue to provide the people with a stable life and successfully step up socialist construction." [54]

Kim’s statement manifests the "people first principle" which was embedded in the 2021- 2025 five-year national economic development plan adopted by the WPK in January 2021. The "people first principle" dictates that the demands and interests of the people are to be the top priority of the DPRK government and the WPK. This principle is in contrast with the "military-first politics" (Songun politics) prioritizing the Korean People’s Army, which had been the guiding ideology of Kim Jong Il.

Under the "people first principle", the government and the WPK are responsible for securing a stable supply of food for the people.

Since July 2021, reports from the Korean Central News Agency and Rodong Sinmun have increasingly emphasized the importance of the efforts by the government and the WPK to secure an adequate harvest despite the severe weather conditions and natural hazards. [55] The statement by Kim Jong Un and the DPRK news reports show that the leaders consider that food security has become indispensable for solidifying the political and social stability. [56]

In order to ensure a stable supply of food, the DPRK will need to rely on imports from China and other countries of food and other items associated with agriculture and food production, which will require the DPRK to prioritize strengthening its diplomatic relationships with those countries, especially China.

Conclusion

As of mid-2021, the DPRK's food supply system appears to have been significantly constrained, especially due to the land-based border closures and the lockdown of cities. Certain regions reportedly experienced severe problems. Nevertheless, available information suggests that the food shortage is not a nationwide phenomenon but rather a regional one, impacting in particular the inner northeastern regions whose economies rely on land-based trading with China.

The DPRK's food security has been significantly affected by the lack of trade with China. The DPRK's domestic food supply and production have also faced considerable problems. Fishery operations appear to have been suspended for quite some time in 2020 and 2021. While fishery operations reportedly resumed in June or July 2021, the DPRK might need more time until the fishing vessels return to full operation.

As for crop harvesting, the DPRK has suffered from a chronic lack of foreign-sourced essential agricultural items, including machinery and seeds, which has resulted in low yield estimates for rice and certain crops in 2021. Harvesting will be also negatively affected by severe weather conditions, such as drought, and the heavy rainfall and flooding in the coming months. FAO has estimated a gap of domestic supply and demand of certain crops, and noted the need for the DPRK to resume import of commercial commodities and receive food aid in order to fill the gap.

The DPRK will not likely resume importing food and foreign-sourced items unless the country feels confident in the effectiveness of its counter-pandemic measures to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus, including the vaccination of its population. Therefore, the speed with which counter-pandemic measures are implemented will likely affect the DPRK's efforts to secure stable food supply and production.

The DPRK will need to prioritize strengthening diplomatic relationship with other countries, especially China, in order to ensure stable import of food and associated items.

To summarize, the DPRK's food security hinges on multiple factors, including the resumption of trade, weather conditions, counter-pandemic measures and the country's diplomatic relationship with China and other countries. Food security will continue to be a dominant issue for the DPRK government and the WPK.

ONN will continue to monitor the food security situation in the DPRK.

[1] For example, in July, Radio Free Asia reported, based on information from residents in the eastern coastal city of Wonsan, that at least three ethnic Chinese residents in the city had passed away due to starvation between January and June 2021. See, North Koreans Alarmed by Starvation Deaths of Well-Off Ethnic Chinese Once the Envy of their Neighbors, Chinese "Hwagyo" are now starving like the poorest citizens, Radio Free Asia, 20 July 2021, available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/hwagyo-07202021220452.html

[2] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Commodity Intelligence Report, 27 July 2021

[3] Since December 2017, all UN Member States have been prohibited from exporting to the DPRK industrial machinery pursuant to UN Security Council resolution 2397 (2017). See paragraph 7 of S/RES/2397 (2017), available at: https://undocs.org/S/RES/2397(2017)

[4] 3rd Plenary Meeting of 8th Central Committee of the WPK Opens, KCNA, 16 June 2021

[5] Colin Zwirko, North Korea admits "food crisis", says grain to be distributed to population, NK News, 20 June 2021, available at: https://www.nknews.org/2021/06/north-korea-admits-food-crisis-says-grain-to-bedistributed-to-population/?t=1636636757375

[6] The United Nations, A/ HRC/46/51, 1 March 2021, paragraph 39, available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/KP/A_HRC_46_51_advance_unedited_version.pdf

[7] The Global Network against Food Crises, Global Report on Food Crises – 2021, p. 11, available at: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP0000127343/download/?_ga=2.113764047.918875645.1627590844-282396973.1627590844

[8] Russian Ambassador to North Korea: Russian diplomats are not afraid of the hardships of the coronavirus blockade, TASS, 14 April 2021, available at: https://tass.ru/interviews/11146461

[9] Asia Press is a Japan-based platform for Asia Press International, a group of freelance photojournalists who are based in more than ten countries and regions. Asia Press's reports on DPRK-related affairs have been led by Jiro Ishimaru and Lee Jinsu, who receive information from "reporting partners" living in the DPRK. Asia Press publishes news articles in English on its website "RIMJIM-GANG" which in English translates as "Asia Press North Korea report."

[10] Jiro Ishimaru, The Reality and Causes of the Deterioration of the People's Welfare (1) Residents Impoverished by Excessive Coronavirus Quarantine, News from Inside North Korea, RIMJIN-GANG, 8 July 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/2021/07/politics/cause/

[11] According to Asia Press, DPRK authorities intensified a crackdown on radio wave communication in 2020. See, Jiro Ishimaru, Inside N. Korea: The Reality and Causes of the Deterioration of the People's Welfare (1) Residents Impoverished by Excessive Coronavirus Quarantine. RIMJIN-GANG, 8 July 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/2021/07/politics/cause/

[12] North Pyongang Province is also located along the border with China, but on the Western coast.

[13] Each figure represents an average of prices in the DPRK's North Hamkyung Province, Ryanggang Province and North Pyongan Province. In deriving the figures for 29 June and 8 July 2021, Asia Press excluded prices from Hyesan in the Ryanggang Province on the ground that they were exceptionally high compared to the other cities. See, https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/north-k-korea-prices/

[14] Asia Press reported an average price for commodities available in the DPRK's North Hamkyung Province, Ryanggang Province and/or North Pyongan Province. See, https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/north-kkorea-prices/

[15] Market Trends, Daily NK, available at: https://www.dailynk.com/english/market-trends/

[16] Park, Young-Ja, Kim, Jin-Ha, Jeong, Eun Mee, and Choi, Ji Young, Analysis and Response to the 3rd Plenary Meeting of the 8th Term of the Central Committee of the WPK, Korea Institute for National Unification, Online Series, 22-06-2021, CO 21-18, p. 6, available at: https://www.kinu.or.kr/pyxis-api/1/digital-files/c9fab5fe60ff-4d39-804c-ee2baf490833

[17] KCTV, 20 June 2021, video footage from 8:30:08 to 8:32:15, available at: https://kcnawatch.org/kctvarchive/60cf44323712f/

[18] Latest Market Price Index Inside N.Korea, Asia Press, 8 July 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/north-k-korea-prices/

[19] A Mysterious 33% Surge in the Won Against the Chinese Yuan…Are the Authorities Manipulating N. Korea's Currency?, RIMJIN-GANG, 8 June 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjingang/2021/06/society-economy/rate/. Reportedly, the DPRK authorities previously prohibited the use of foreign currencies in the domestic market as well. See, for example, Takeshi Kamiya, 北朝鮮、市場での外貨使用を禁止 両替商処刑の情報も (North Korea Bans Use of Foreign Currency in Markets, Reports of Execution of Money Changers), Asahi Newspaper. 28 December 2020, available at: https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASNDX67C2NDSUHBI01V.html

[20] Seulkee Jang, US dollar and Chinese renminbi plummet against North Korean won once again The rise of corn and rice prices has led to increasing concern among ordinary North Koreans, 9 June 2021, available at: https://www.dailynk.com/english/us-dollar-chinese-reminbi-plummet-against-north-korean-won-onceagain/

[21] The United Nations, A/ HRC/46/51, 1 March 2021, paragraph 39, available at: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/KP/A_HRC_46_51_advance_unedited_version.pdf

[22] The value of Chinese exports to the DPRK was US$ 4,098 in January 2021 and US$ 3,401 in February 2021.

[23] 13th Plenary Meeting of 14th SPA Standing Committee Held, Rodong Sinmun, 4 March 2021

[24] For example, see, Keisuke Fukuda, 経済悪化に耐えきれず北朝鮮が国境を開放へ 中国・丹東での貿易を本格化させるが人的交流はまだ先 (North Korea, Unable to Endure Economic Downturn, Opens Its Borders to Trade in China's Dandong in Earnest, but Human Exchange Still Lies Ahead), Toyo Keizai, 3 March 2021, available at: https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/414815

[25] Keisuke Fukuda, 北朝鮮の生命線「中朝国境」はいつ開放されるか (When will the Sino-DPRK border, North Korea's lifeline, be opened?), Toyo Keizai, 17 June 2021, available at: https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/434649

[26] The Chinese customs statistics, available at: http://43.248.49.97/indexEn

[27] This finding was based on data from Peking University's DPRK-China border field research team (June 11, 2021). See, Eun-Lee Joung, Is the North Korean Economy Under Kim Jong Un in Danger? "Arduous March" in the Age of COVID-19?, 38 North, 13 July 2021, available at: https://www.38north.org/2021/07/is-the-northkorean-economy-under-kim-jong-un-in-danger-arduous-march-in-the-age-of-covid-19/#_ftn4

[28] 北朝鮮 コロナ対策の国境封鎖 今月中にも制限の一部緩和か (North Korea may partially ease restrictions related to the anti-corona border blockade sometime this month), NHK, 15 April 2021, available at: https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20210415/k10012976591000.html

[29] Mitsuhiro Mimura, 北朝鮮が再度の「食糧危機」を対外発信する本当の事情 (The real reason why North Korea is announcing another "food crisis" to the world), Weekly Diamond, 14 July 2021, available at: https://diamond.jp/articles/-/276685. The observations and analysis by Mimura are based on his correspondence with DPRK counterparts, including multiple DPRK economists.

[30] Colin Zwirko, North Korea turns airport into COVID-19 disinfection center to boost trade, 16 April 2021, available at: https://www.nknews.org/pro/north-korea-turns-airport-into-covid-19-disinfection-center-toboost-trade/; and Colin Zwirko, North Korea eyes China trade restart as COVID-19 import zone activity ramps up, 29 July 2021, available at: https://www.nknews.org/pro/north-korea-eyes-china-trade-restart-as-covid-19- import-zone-activity-ramps-up/

[31] North Korea bans entry into Pyongyang to prevent coronavirus spread, Kyodo News, 27 November 2020, available at: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2020/11/a41603955fa5-n-korea-bans-entry-intopyongyang-to-prevent-coronavirus-spread.html

[32] Reportedly, illicit trade between China and the DPRK involving military-linked companies was rampant due to economic difficulties. In the process of cracking down on illicit trade, suspected cases of COVID-19 infection were detected in Hyesan and Sinuiju. This incited Kim Jong Un’s decision to fire two members of the Presidium of the Political Bureau of the 8th Central Committee of the WPK who had been high-profile military officials, Ri Pyong-chol and Pak Jong-chon. Reportedly, Kim Jong Un had criticized Hyesan as well, saying that "the city is full of illegal activities", before directly ordering for the lockdown. See, Yoshihiro Makino, 北朝鮮の党最高幹部、突然の解任 金正恩氏は何に怒ったのか (North Korea's Top Party Officials Suddenly Dismissed: What Made Kim Jong Un Angry?), The Asahi Shimbun Globe, 30 June 2021, available at: https://globe.asahi.com/article/14384601. See also Lockdown Death Toll Climbs in Hyesan: "We are Dying Due to Lack of Medicine and Food", Asia Press Network, 24 February 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/2021/02/society-economy/interview-4/; and Ri Pyong-chol fired by Kim for negligence, Joongang Ilbo, 14 July 2021, available at: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2021/07/14/national/northKorea/North-Korea-Covid19-RiPyongchol/20210714163900303.html

[33] Lockdown Death Toll Climbs in Hyesan: "We are Dying Due to Lack of Medicine and Food", Asia Press Network, 24 February 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/2021/02/societyeconomy/interview-4/

[34] Reportedly, the price of frozen pollack rose from 5,500 won per kilogram just before the pandemic to 50,000 won, but that it subsequently declined to 25,000 won. See, Eun-Lee Joung, Is the North Korean Economy Under Kim Jong Un in Danger? "Arduous March" in the Age of COVID-19?, 38 North, 13 July 2021

[35] The Government of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Voluntary National Review on the Implementation of the 2030Agenda for the Sustainable Development, June 2021, available at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/282482021_VNR_Report_DPRK.pdf

[36] Ibid., p. 48

[37] U.S. Department of Agriculture, Commodity Intelligence Report, 27 July 2021

[38] Quarterly Global Report: CROP PROSPECTS and FOOD SITUATION, FAO, July 2021, available at: http://www.fao.org/3/cb5603en/cb5603en.pdf

[39] EU Science Hub, European Commission, Anomaly Hotspots of Agricultural Production, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, available at: https://mars.jrc.ec.europa.eu/asap/country.php?cntry=67. See also, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Commodity Intelligence Report, 27 July 2021, available at: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/highlights/2021/07/NorthKorea/index.pdf

[40] In April, the DPRK's import of disodium carbonate, urea, diammonium phosphate, insecticides, fungicides and herbicides had a share of about 56% of the total import. In May 2021, the DPRK’s import from China of urea and diammonium phosphate had a share of about 75% of the total import. Source: the Chinese customs statistics

[41] The U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that in 2021 the rice yield forecast was below the 5-year average yield expectations, while the corn yield forecast was almost the same as the long-term average expectation. See, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Commodity Intelligence Report, 27 July 2021

[42] Reportedly, the precipitation levels of 583 mm and 308 mm respectively, between 18:00 on 1 August and 19:00 on 2 August. These precipitation levels far exceed the historical averages. See, 주체110(2021)년 8월 5일 중앙텔레비죤 20시보도 (Juche 110 (2021) August 5, Central TV 20 hour report), KCTV, 5 August 2021, aired at 20:13-20:20, available on YouTube, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGwTP4LSWVM

[43] Colin Zwirko has already found flooding to have occurred in the early days of August 2021 in small towns along major rivers in North and South Hamgyong provinces. See, Colin Zwirko, Crises mount in North Korea as major flooding follows drought, food shortages: Satellite imagery reveals flooded homes and broken bridges from severe August rains, NK News, 4 August 4, 2021, available at: https://www.nknews.org/2021/08/crisesmount-in-north-korea-as-major-flooding-follows-drought-food-shortages/

[44] The Democratic People's Republic of Korea Food Supply and Demand Outlook in 2020/21 (November/October), FAO, 14 June 2021

[45] The Chinese customs statistics, available at: http://43.248.49.97/indexEn

[46] Not only is butter expensive, but it needs to be stored in a refrigerator, which is not easy for most DPRK residents because of the unstable electricity supply. See, Je Son Lee, Chinese cheese and Russian butter: How to eat dairy in North Korea; Do you eat dairy products such as milk, cheese and butter in North Korea, too?, NK News, 29 August 2016, available at: https://www.nknews.org/2016/08/chinese-cheese-and-russian-butter-howto-eat-dairy-in-north-korea/

[47] Eun-Lee Joung, Is the North Korean Economy Under Kim Jong Un in Danger? "Arduous March" in the Age of COVID-19?, 38 North, 13 July 2021, available at: https://www.nknews.org/2016/08/chinese-cheese-andrussian-butter-how-to-eat-dairy-in-north-korea/

[48] Mitsuhiro Mimura, 北朝鮮が再度の「食糧危機」を対外発信する本当の事情 (The real reason why North Korea is announcing another "food crisis" to the world), Weekly Diamond, 14 July 2021

[49] Inside N. Korea: Residents Relieved as Authorities Distribute Emergency Food Supply of 5-7 Kilograms of Corn, The Asia Network Press, 20 July 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjingang/2021/07/society-economy/distribute/

[50] Latest Market Price Index Inside N.Korea, The Asia Network Press, 4 August 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/north-k-korea-prices/

[51] DPRK authorities reportedly released rice for military and emergency reserves. See, Residents Relieved as Authorities Distribute Emergency Food Supply of 5-7 Kilograms of Corn, Rimjin-Gang, 20 July 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/2021/07/society-economy/distribute/. On 8 July, the ROK National Intelligence Service also briefed the ROK Parliament about the emergency release of the military's rice reserve. See, Junichi Toyoura, 北朝鮮「重大事件」で解任は軍トップの李氏…韓国国情院「消毒施設不十分と関連 (North Korea's top military official, Ri, dismissed in "major incident" ... South Korea's State Intelligence Agency says it is related to inadequate disinfection facilities), Yomiuri Newspaper, 10 July 2021, available at: https://www.yomiuri.co.jp/world/20210709-OYT1T50054/

[52] Latest Market Price Index Inside N.Korea, The Asia Network Press, 4 August 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/north-k-korea-prices/

[53] Latest Market Price Index Inside N.Korea, The Asia Network Press, 20 July 2021, available at: https://www.asiapress.org/rimjin-gang/north-k-korea-prices/

[54] 3rd Plenary Meeting of 8th Central Committee of WPK Opens, KCNA, 16 June 2021

[55] For example, see, DPRK Makes All-out Efforts to Avert Drought Damage to Crops, KCNA, 1 August 2021

[56] On 7 July 2021, Radio Free Asia reported information from DPRK residents that the WPK's Central Committee had outlined a policy to prepare for long-term food shortage and had sent a directive to the Provincial Party Committee, which instructed organizations at all levels, businesses and units in the province to solve the food shortage problem on their own. See, Facing Chronic Shortfalls, North Korea Tells Citizens to Start Supplying Their Own Food, People say government is passing on its responsibilities to them, Radio Free Asia, 7 July 2021, available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/korea/food-07072021183519.html. If true, it is unclear how this directive was positioned in the context of the people first principle.